Previously I wrote about the fact that adoptees can’t be certain future generations will understand their biological origins unless they take action to ensure this information is preserved. I began to think about this issue due to a discovery I made while trying to determine whether my husband descends from one or the other of two branches of the same surname in the Basilicata region of Italy.

Building out the family tree of one of the lines led to a man I’ll call Antonio B. who was born in 1884. I first found Antonio B.’s 1902 marriage record via Family Search, which states that he was “figlio di padre ignoto . . . e di madre ignota” (son of father unknown . . . and of mother unknown). After his marriage, though, he had emigrated to New York, and I’d found an alleged birth date for him, so I decided to pursue his Italian birth record.

His civil birth record was also available on Family Search. At this point in my experience as an amateur genealogist, I had only recently learned how to search and begin to interpret Italian records. The birth record I found was entirely handwritten, and it was difficult to make out some of the Italian words. I did know by then how to look for important dates, names, and locations, but this record seemed to have significantly more verbiage than I’d seen on similar records. Thanks to my (rusty) knowledge of Spanish and to Google translate, I could make out some of the Italian well enough to begin to get an idea of what it might say, but I couldn’t figure out enough of the handwritten words to get a clear sense of what the document was trying to tell me.

Thankfully, the wonderful Genealogical Translations group on Facebook came to my aid and provided a full translation (minus a few words where the handwriting couldn’t be deciphered):

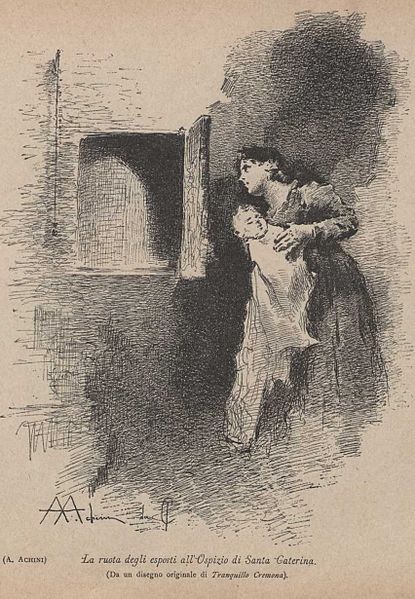

Mariarcangela . . . the receiver of foundlings, presented a male baby, about 7 hours old, found . . . at 3:30 this morning in the foundling wheel at her house . . . lying on its back with both hands covering his face. The infant was assigned the name Antonio and surname [withheld here for privacy] and the informant was instructed to assign the baby to a wet nurse who would be accountable to the authorities for his care.

Though I’d never before heard of a “foundling wheel,” I knew based on personal experience that I’d reached a dead end. Foundling wheels, it turns out, were the original baby boxes—a means by which women could abandon newborns (and sometimes older infants) anonymously. Here’s a vivid description from the genealogy website of an unrelated Italian family:

The wheel was a kind of “lazy Susan” that had a small platform on which a baby could be placed, then rotated into the building, without anyone on the inside seeing the person abandoning the child. That person then pulled a cord on the outside of the building, causing an internal bell or chimes to ring, alerting those inside that an infant had been deposited. In the larger towns, foundlings were baptized, then kept in a foundling home with others, and fed by wet-nurses in the employ of the home. There they may have stayed for several years until they were taken by townspeople as menial servants or laborers, or placed with a foster family. Or, sadly but more likely, they never left the institution, having died from malnutrition or from diseases passed on by the wet-nurses.

In smaller towns, the foundling wheel may have been in the wall of the residence of a local midwife. She would have received the child, possibly suckled it immediately to keep it alive, or arranged for a wet-nurse to do so, then taken it to the church to be baptized and to the town hall to be registered. She then consigned a wet-nurse living in or near the town to take the child and provide sustenance, for a monthly stipend paid by the town. If the child was near death when found, many midwives were authorized by the church to baptize the infant, “so that its soul would not be lost.“

That website offers a ton of other information the author learned about children deemed illegitimate in Italy, as does the Family Search Wiki:

From about the thirteenth century through the end of the nineteenth century, throughout the areas that in 1860 became unified Italy, a pregnant single woman, faced with the loss of her own and her family’s honor, would leave her residence to give birth elsewhere and after having the baby baptized, would give (or have the midwife give) the newborn baby to a foundling home (ospizio) to be cared for by others.

[…]

The Italian infant-abandonment system generally but not always included the assignment of a surname to the infant upon arrival at the ospizio. Thus while in the ospizio and later when placed with a family in the countryside, the child bore a surname different from its unknown family of origin and different from the family with which it was placed. . . .it would be assigned a surname used locally for foundlings . . . For the most part the new surname was used by the child throughout the remainder of its life . . .

Antonio B.’s assigned surname is an Italian word that may be a descriptor of his father’s appearance, but we’ll never know for sure. The Family Search Wiki article goes on to list many examples of known surnames that were routinely assigned to Italian foundlings. Some of these turn out to be common Italian American surnames, and I spot several that I recognize from elsewhere in my husband’s family tree. According to one study, there were 1,200 foundling wheels in Italy by the mid 1800s.

Why the need for so many foundling wheels? Why were so many babies being abandoned? The reasons then were similar to the reasons now, the primary reasons being poverty and the shame of childbirth outside of wedlock as imposed by religion, in this case Roman Catholicism. Consider this excerpt, purportedly from the “original Catholic Encyclopedia, published between 1907 and 1912”:

Illegitimate offspring are designated by various names in canon law, according to the circumstances attending their procreation: they are called natural (naturales) children, if born of unmarried persons between whom there could have been a legitimate marriage at the time either of the conception or the birth of their offspring; if born of a prostitute, illegitimate children are called manzeres; if of a woman who is neither a prostitute nor a concubine, they are designated bastardi; those who are sprung from parents, who either at the time of conception or of birth could not have entered into matrimony, are termed spurii; if, however, valid marriage would be impossible both at the time of the conception and of the birth of the children, the latter are said to be born ex damnato coitus: when one parent is married, the illegitimate children are called nothi; if both are wedded, adulterini; if the parents were related by collateral consanguinity or affinity, incestuosi; if related in the direct line of ascent or descent, nefarii.

The specificity of this terminology blows my mind, despite my thirteen years of Catholic school. What purpose does it serve to ostracize people this way? I wish it were true that humanity was more enlightened in the year 2024, but unfortunately there are still factions that cling to so-called moral categorizations of people in order to maintain hierarchies of power.

Although foundling wheels were outlawed in Italy in the early twentieth century, they have made a return there, just as baby boxes have proliferated here in recent years. Those who oppose abortion are especially prone to encouraging unexpectantly pregnant women to use these devices, though they’re not so supportive of providing these women with the resources they need to be able to parent their own children.

Antonio B. is not on my husband’s ancestral line after all, yet he is the forefather of an Italian American family that will likely never be able to learn their extended history beyond him, all because of a system that deliberately cut him off from his rightful family because of the circumstances of his birth. As a society, we don’t have to accept this type of system going forward, but will we ever have the collective fortitude to reject it once and for all?

I long for a world in which all people can truly live and let live without judgment.

Image 1: Ruota – Chiostro di San Gregorio Armeno (Napoli); photo taken 24 July 2018 by Ruthven (via Wikimedia Commons)

Image 2: Ruota degli Esposti; photo taken 28 March 2015 by Peppe Guida (via Wikimedia Commons)

Image 3: La ruota degli esposti all’Ospizio di Santa Caterina tratto da l naviglio : strenna del Pio Istituto dei Rachitici di Milano; 1886 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Leave a comment